Should you search online the meaning of derelict places in urban environments, there is a fair chance to be directed towards brownfields, the way they may contribute to urban master plans (1) and how their potential translates in operational practicalities (2). No doubt that you will also be directed towards historical sites’ survival to disasters. Aesthetic and emotional engagement will be undoubtedly crucial in the way such legacy is recognized and preserved.

Far behind, some ancient urban ruins, orphan of the passing time, seem condemned to a museumification at best or to indifference at worst.

But how could we define a ruin? Why do we admire some of them, protecting and restoring them, sometimes giving them a new life, when others are left in oblivion? Obviously, the meaning we give to ruins will be key in deciding if they deserve our collective recognition. Historians will emphasize their historical record, artists will remind us of past greatness depicting scenes (3) while others will engage in an in-depth analysis of the “ruin-porn” development (4). Ultimately, we don’t really know what to do with ruins and what to think of them. Beyond the age-old argument of the transience of life, ruins can be prized for their aesthetic value without any historical authenticity (5); they can be events’ remembrance of mankind’s madness without knowing if this will engage into positive perspectives; they can be seen for their symbolic significance, but which one exactly and how impacting would it be for the daily lives of urban dwellers?

In his publication (6), A. Le Blanc questions whether ruins due to disasters may generate, through the message they convey, the required risk awareness to improve urban resilience. But as stated by A. Le Blanc, preserving a ruin is a marker of the event’s memory which do not always contribute to a risk management culture when requirements to understand risk assessments are missing. The author’s analysis can be hardly criticized. But the vulnerabilities shaping the emergence of disasters (7) and how we perceive them (8) are issues which also need to be addressed, when deciding to include the presence of ruins in a resilient thinking approach. The story of Pompei would not be complete when forgetting to explain that most casualties were counted amongst those who did not have the financial means to escape the eruption (9).

How useful can ancient ruins be in urban spaces? How could they possibly be engaged into a process enabling to withstand shocks, to integrate the occurrence of hazards, to recall to non-expert citizens that urban spaces are dominated by socio-ecological dynamics? At a time when resilience is often used to justify investments in infrastructures without any analysis of the social advantages provided to the most vulnerable of us, is there any chance for a ruin to be something else than “just a ruin”?

The case of Gemona, IT, cited in A. Le Blanc publication, provides some interesting insights. The city was severely damaged by an earthquake in 1976. Beyond the lessons learned in terms of seismic criteria improvement and building protection, the preservation of the church remaining ruins fostered their inclusion within the university campus area, “revitalizing” the place. Though, understanding that the problematic of ruins is at the heart of the relationship between past, present, and future is crucial to appraise their role in an urban construction. As quoted by C. DeSilvey & Al (10), “what and how we choose to preserve often tells us much more about our values in the present than about the past and the people who inhabited it”. To this respect, artist Robert Smithson (11) developed a worthwhile approach, reconsidering the value of ruins through his concept of “Ruin in Reverse” based on the idea that “buildings do not fall into ruin after being erected, but they rise into ruin even before they are.”

Ancient ruins are typical of an architecture with no functionality; at the same time, the strength of their presence talks to us. But this language is paradoxical. On one hand, their persistence in time leads us to think in terms of urban resilience, at least when defined by the capacity to survive the passing time. But on another hand, a ruin is far from being the best example to engage in resilient thinking when only seen from its pure physical perspective. Many authors make a difference between post-disasters and historical ruins but all of them have one point in common. Time is no longer their “raison d’être”. They have lost their initial functionality and by becoming what they are, they have acquired a new status with no guarantee on the meaning we will give them in the coming centuries. As said by T. Baillargeon (12), some of them are “in-between” spaces, ephemeral objects of which current significance depends on what we will decide for their future. They conjure up the passing time, not to evoke a nostalgia or any romantic feeling, but to question our destiny. And by doing so, they help us to understand the meaning of ephemerality. They oppose the idea of time aiming at truth; they help to reconsider what is taken as granted when needed and to acquire this critical thinking which hopefully will lead to improve urban resilience.

“Only the ephemeral is of lasting value.” Eugène Ionesco, playwright, 1909-1994

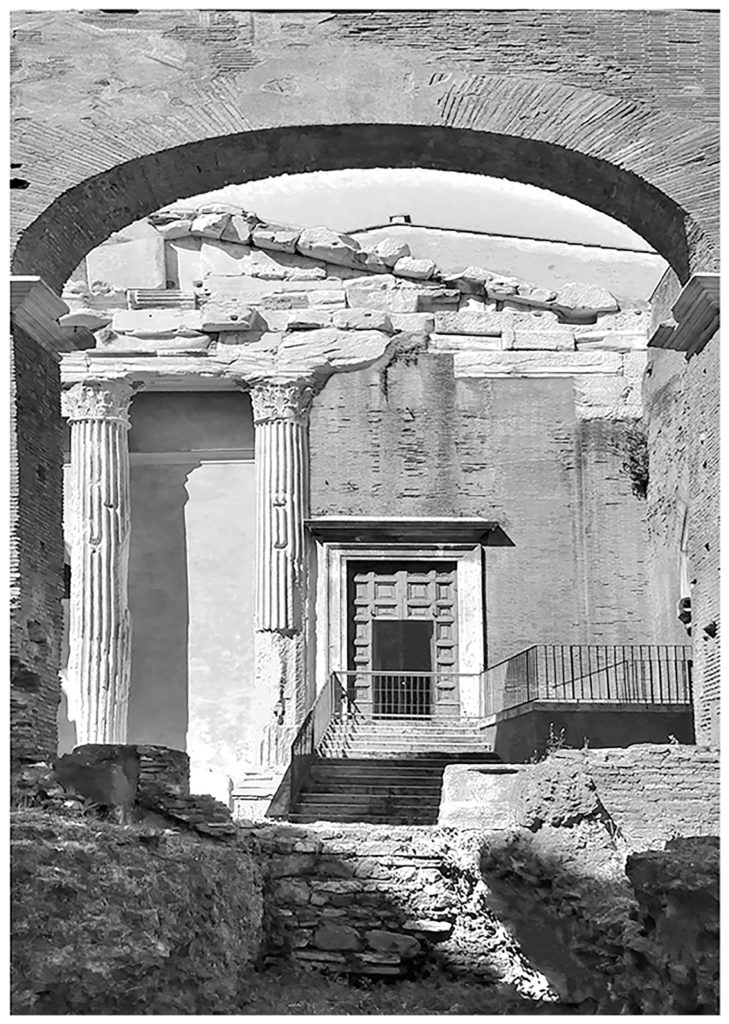

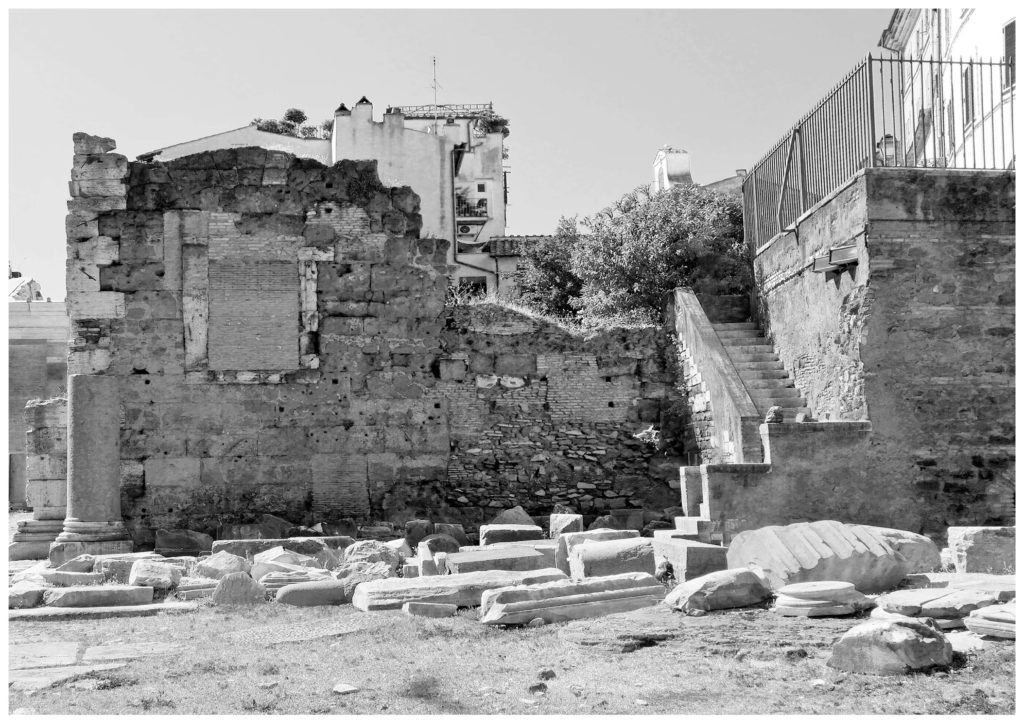

The three below works have been inspired by photographs taken in the Jewish ghetto of Rome, IT. They challenge the myth of “The Eternal City”, questioning the continuity suggested by a metaphor ignoring socio-cultural disruptions. Echoing my own technique with argentic paper darkening in time, as an allegory of ephemerality, the pictures show how ruins in contemporary urban spaces can be left in “in-between” stages.

More on the photographic work can be found here

- http://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2013.795332

- https://www.cerema.fr/en/actualites/cerema-launches-trial-app-help-compile-national-directory

- https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/ruin-lust

- https://averyreview.com/issues/18/notes-on-ruin-porn

- https://www.newgeography.com/content/003659-genealogy-of-rust-belt-chic

- https://www.cairn.info/journal-espace-geographique-2010-3-page-253.htm

- llan Kelman, Disaster by Choice, How our actions turn natural hazards into catastrophes, Oxford University Press

- https://www.resi-city.com/2020/10/04/the-sense-of-vulnerability/

- https://www.persee.fr/doc/ahess_0395-2649_1973_num_28_2_293352 (pages 375-376)

- https://www.uclpress.co.uk/products/125034

- https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/biography-robert-smithson

- https://www.cairn.info/revue-societes-2013-2-page-25.htm