The concept of urban resilience is a source of engagement, creativity, and inspiration for everyone committed to improve our daily urban lives. But when concepts are not contextualized, and especially when “resilient programs” are brought to the forefront by local decision makers without in-depth analysis, other questions arise, most often linked to trade-offs political acceptability. The below thoughts and photographic work, inspired by my recent trips, aim to engage in an opened thinking on such issues.

Vancouver, CA, ranks among the so-called “most beautiful cities in the world”. Recently finalist for the 2021 Wellbeing Cities Award (1), the city is presented as the example of bottom-up initiatives improving sustainability and building resilience. And there is obviously no reason to doubt of the townhall good faith when launching the program “Places for people” aiming to shape the public realm in downtown Vancouver over the next 30 years (2). As one of the most striking examples of a true commitment towards a model of sustainable community, UniverCity (3-4), adjacent to the Simon Fraser University, shows how a resilient and sustainable-minded approach could meet the community expectations in terms of academic and governance development.

Unfortunately, Vancouver is also the worse example you could think of when evaluating its scope to reach the sole and only goal of urban resilience: improving the well-living and wellbeing of citizens together. Homelessness (5) is not only present. It is part of the city metabolism. Simply walking downtown will show you how the ongoing process of gentrification coupled with the absence of social housing could develop into a humanitarian disaster.

Beyond the adverse effects of market driven logics, the question is how a well-educated society cannot see the consequences of such failure. In their publication on specific and general resilience trade-offs for the Vancouver area, L. Yumagulova & I. Vertinsky (6) develop a critical view on the governance and the required conditions to implement a planning for floods and sea-level rise. How relevant could such weakness be in explaining the inability to consider housing as a human right?

On another matter deeply rooted in the colonial history of Vancouver and its area, and how this interferes with societal perspectives, L. Yumagulova addresses the issue of multiscale governance, highlighting the consequences of our neo-colonialist system and how indigenous communities are discriminated (7). Building on the concept of “riskscapes,” allowing a better understanding of how risks are distributed in the fields of natural hazards, health inequities, climate change, political violence and state failure, the author shows how the inequitable distribution of risks can deepen First Nations vulnerability.

The historical rights of indigenous communities on their dispossessed land are nowadays recognized. First Nations culture based on diversity, beliefs, spirituality, and connections to nature has survived. The potlatch ceremonies (8), once banned by the Canadian government, could be a source of inspiration and an opportunity made for a genuine dialogue between indigenous and non-indigenous communities. And at the same time, a way to give to the word “inclusivity” its true meaning. Vancouver cultural heritage is intrinsically linked to the legacy of First Nations and should recognize the meaning of such value. It has no other option. It is great time for this city to engage in a critical self-assessment if it wants to be more than simply counting among the “most beautiful cities in the world”.

8 000 km east, the city of Bilbao, ES, described by its current mayor as once “grey and sad” (9), turned out into one of the most applauded resilient cities. From blossoming during the late 19th and early 20th century, driven by the development of steel, mining and port operations, the urban model of Bilbao collapsed, severely affected by the financial turmoil of the 1970’s. As with other European industrial cities, high unemployment, and environmental damages due to polluting industries became Bilbao’s markers. Moreover, flooding is an on-going threat to the city. The 1983 disaster (10) may well be followed by others, as detailed in the EU-Resin assessment report (11).

Today, if you walk by along the sides of the river Nervion, many words will come up to your mind, but certainly not “grey and sad”. The strategy implemented to bring Bilbao to a new life has been thoroughly documented (12). The Guggenheim Museum stands as the new flagship of the city where rusted vessels ended up their lives some decades ago. The transformation is impressive. Northwest of the center, the opening of the Deusto Canal aims to reshape a former peninsula, known for its past industrial and harbor activities, into an artificial island. The “Zorrozaure project” (13), advertised as the “Manhattan of Bilbao,” and designed by Zaha Hadid Architects, is expected to fully restore a derelict site into a new, regenerated quarter, including affordable housing, social and cultural facilities, and flood prevention measures. But here and there, unexpected voices arise to recall that the legacy of the city, more than just being remembered, should be part of future master plans. Recalling “ethnographic urbanism” practices, Isusko Vivas publication (14) questions how such project could reflect the imaginary identity of the area, once vibrant through its population of artisans, freighters, and sailors. And what will be the future of the current diverse population, counting alternative social and artistic movements settling temporarily in abandoned buildings, who undoubtedly contribute to the ephemeral though essential urban life dimension? Artist Antoni Muntadas, with his exhibition “The empty city” (15), building on philosopher Walter Benjamin quotes, echoed the same questions.

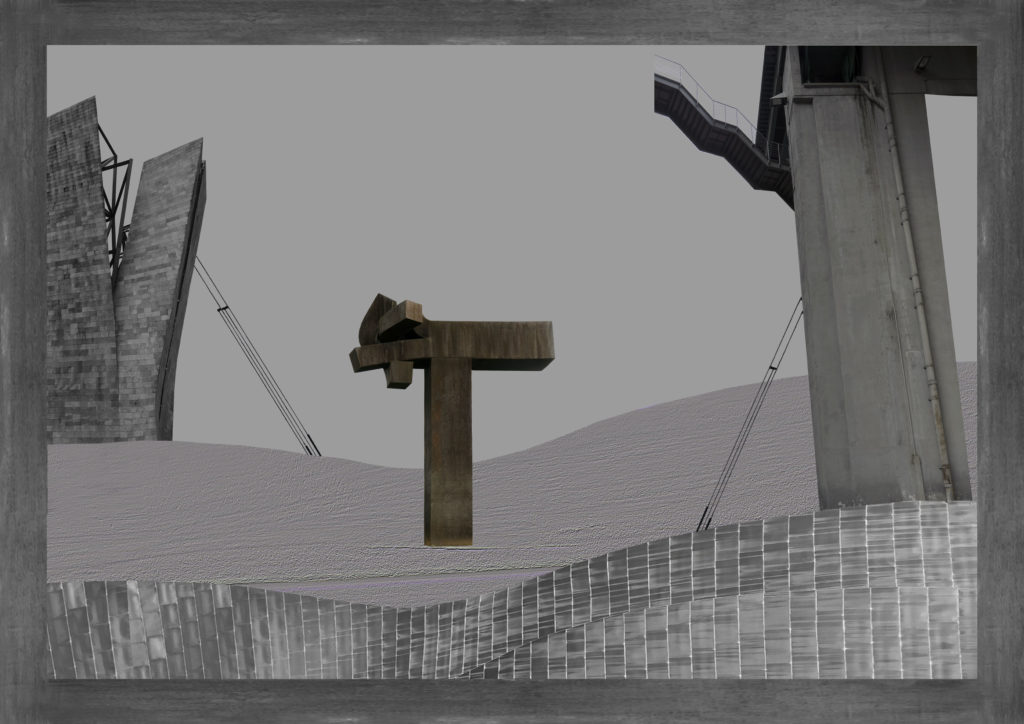

From Vancouver to Bilbao, from the First Nations legacy to the industrial past of the Biscay, cultural heritage seems to be the missing piece of the resilient puzzle. Rooted in social fights, this heritage has left an indelible mark on our collective awareness and deserves more than a secondary role. Building on the groundwork of the Sense of Place (16), this intangible legacy translates into art pieces contributing to a universal remembrance going far beyond simple exhibits. In this respect, the sculptures of Eduardo Chillida (17), do not speak only of the Basque country industrial heritage, but reach a spiritual dimension combining in one strength the intangibility of space and the materiality of steel. From Vancouver to Bilbao, from the First Nations legacy to the industrial past of the Biscay, cultural heritage speaks of the values that will enable us to face adverse times.

In the below work, Lotura XXXII (18), recalling the steel industry that built Bilbao’s greatness, stands as an iconic symbol sounding as a First Nations totem pole. Framed by disbalanced infrastructures, in-between past, and future, it questions how cultural heritage contributes to urban resilience.

- https://newcities.org/vancouver-canada-wellbeing-cities-finalist/

- https://vancouver.ca/home-property-development/places-for-people-downtown.aspx

- https://univercity.ca/

- https://www.sfu.ca/sfunews/stories/2018/12/gordon-harris-on-sustainable-urban-planning-and-univercity.html

- https://www.homelesshub.ca/community-profile/vancouver

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0264275121002195?via%3Dihub

- https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsaa029

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potlatch

- Le Monde, October 2021

- https://www.mascontext.com/issues/30-31-bilbao/turning-point-one1983-flooding/

- https://resin-cities.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/D4.1__City_Assessment_Report_Bilbao_ICLEI_2016-02-29.pdf

- http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/3624/1/Bilbao_city_report_(final).pdf

- https://www.mascontext.com/tag/zorrotzaurre/

- https://bit.ly/3vupJoC

- https://www.museobilbao.com/in/exposiciones/muntadas-the-empty-city-293

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11625-018-0562-5

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eduardo_Chillida

- https://www.museochillidaleku.com/en/exposiciones/coleccion-chillida-leku/